accesses since November 29, 2011

accesses since November 29, 2011

copyright notice

copyright notice

link to published version: IEEE Computer, January, 2012

link to published version: IEEE Computer, January, 2012

accesses since November 29, 2011

accesses since November 29, 2011

Identity Theft and Financial Fraud vulnerabilities are exposed at ever-increasing rates these days. No news there. What I find remarkable is the type and variety of these vulnerabilities. As I write this, a news story is breaking concerning the leak of personal information by the YMCA of Metro Atlanta. According to the disclosure letter to their members, “[they] learned on November 9, 2011 of the theft of several computers from the office of our software testing and development vendor…. One of the stolen computers, that was password protected, included information on facility members who were active in 2008 and who had transactions that required bank draft, debit or credit card charges. The data included first name, last name, address, phone number, email, birthdates, and encrypted bank account, debit or credit card numbers…. We deeply regret any concern or inconvenience the theft of these computers may cause you.”

The Atlanta YMCA recommended that the members

This is an interesting story from a number of perspectives, not the least of which is the apparent failure of the “Y” to accept any responsibility for the security breach that may have resulted in the loss of its members' personal information. Note that the lost information qualifies as core components of private personal identifiers (PPI) as defined by the Payment Card Industry (PCI), the banking industry, and as used in federal and state regulations. This is not the stricter, extended definition used by Office of Management and Budget and the National Institute of Standards and Technology who wish to extend the definition to include anything that can uniquely identify, contact, or locate people or enable same, but rather the softer, limited, vanilla version expected of every organization that handles credit and debit cards. Finally, the tenor of the member letter is that it was the 3 rd party vendor who slipped up – as if that absolves the “Y” from responsibility. As far as the “Y” is concerned, the responsibility for further remediation lies entirely with the victims. The latter are going to feel the costs of this mishap for quite some time to come – even if the personal data isn't ultimately used for criminal activities.

To be sure, there are many legal issues involved as well. I have no idea whether the courts would hold the “Y” liable for damages if there are any, or whether it would be found out of compliance with the PCI Data Security Standard, whether the “Y” exercised due diligence in its analysis of risk, etc. These are interesting legal questions, but beyond the scope of this column. I'm interested in the question of how we got ourselves in the position where these things are possible. Our focus here will be on the type and variety of these reported breaches when viewed as a whole.

Our YMCA example is just one of thousands of cases of identity theft and financial fraud reported in the media every year. We routinely collect and analyze such reports in search of a high-level perspective in our lab as a backdrop for our technical work in developing security appliances to help investigate and protect against such crime. The YMCA was this week's event-of-interest. Last week it was a reported hospital website breach that resulted in the public release of 10,000 patient's credit cards. Two weeks ago we referenced the story of 2,000 dental patients' records compromised by a password theft. Last month we reported on a lost backup tape that may have exposed 1.6 million people to ID theft as well as the largest ID Theft bust in U.S. history. (for more examples, see our list at www.itffroc.org/rr.html ). We don't try to cover all security and privacy breaches in the identity theft and financial fraud space. Rather we use mainstream media as our filter – we report on stories that seem interesting and get mainstream media attention. There are a few surprises to be found in our analysis of a recent reporting period. I'll share a few of them, below.

The actual number of identity theft and financial fraud victims can only be estimated. It is understood that many if not most cases go unreported. Some industries (banking and gaming come to mind) go to great lengths to avoid any unnecessary media coverage that suggests that their security has been compromised. Not only is this bad for business, but there is also the ever-present risk that the tag-and-baggers will arrive with a warrant and walk out with the companies hard drives. To my knowledge there has never been definitive research on the extent of under-reporting. Of one thing we may be sure: if modern business and industry isn't specifically required by law (under some fairly parochial legal interpretation of course) to report breaches of customer/client confidentiality, it won't get reported. Add to that the fact that many such breaches go undetected.

However, we do have some ballpark estimates of the extent of losses. Private consultancies (e.g., Gartner, Javelin Strategy and Research) conduct surveys. Consumer groups (e.g., Better Business Bureau) and some government agencies (e.g., Federal Trade Commission) collect information on reported complaints from internal and sometimes external sources. Other government agencies (DoJ, FBI, Secret Service) collect information from investigations. In all of these cases estimates of magnitude are necessarily extrapolations. No one really has an accurate handle on the dollar amount of loss. But there is something of a consensus on the extrapolations. As a rule of thumb, “three orders of magnitude rule” comes pretty close to most estimates: each year something on the order of 1-10 thousand dollars is lost by each of 1-10 million people producing a 1-10 billion dollar losses. This is a staggering amount of white collar crime even by Wall Street Ponzi scheme standards.

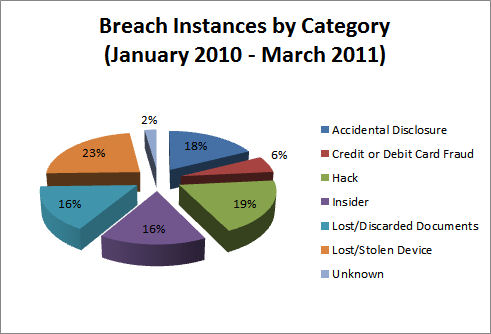

We recently analyzed major data breaches reported by the media for a 15-month reporting period from January 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011. A high-level pass through the data suggested seven major causes of the data loss. Of these, lost or stolen devices (flash drives, laptops, tablets, PDAs, etc.) led the list, with computer or network hacking a close second, followed by lost/discarded documents or physical media, accidental disclosures, and insider threats, in that order. Accidental disclosure of private information would include internal and external data leaks resulting from improper access control, flawed records retention implementation, improper data and media sanitization or destruction prior to equipment re-purposing, ineffective data loss prevention policies and enforcement, and the like.

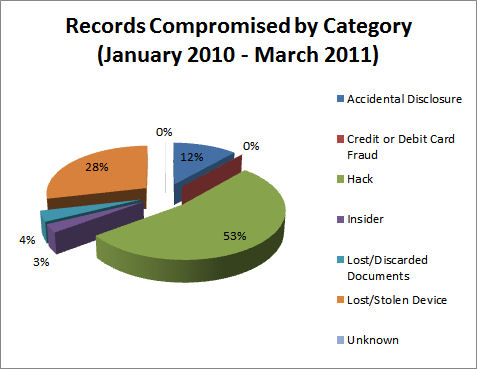

Coarse categorizations of the breaches by cause appear in Figures 1 and 2. Not surprisingly, hacking produces more record compromises per incident than other causes, while the converse is true for data breaches involving physical media.

Figure 1: Number of Breach Incidents by Category (Source: www.itffroc.org)

Figure 2: Number of Records Compromised by Category (Source: www.itffroc.org)

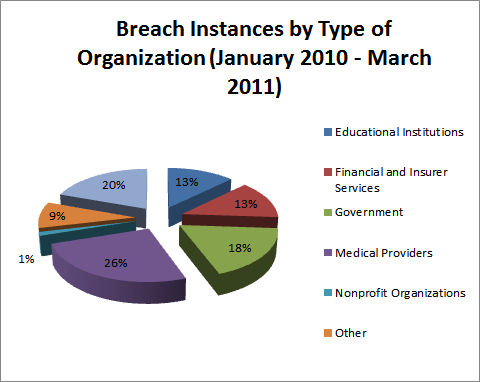

But the most interesting characterization results when one breaks out the breaches by organization type (Figures 3 and 4)

Figure 3: Number of Breach Incidents by Type of Organization (Source: www.itffroc.org)

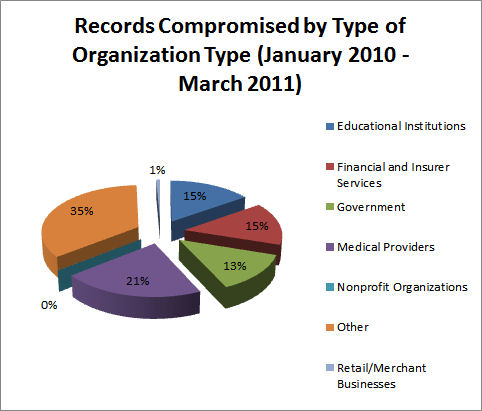

Figure 4: Number of Records Compromised Type of Organization (Source: www.itffroc.org)

A quick glance at the figures indicates that the lion’s share of the data breaches was produced by ‘inviolable’ institutions: banks, healthcare, colleges and our own governments. If we can’t trust them to protect our privacy, who can we trust? Ignoring the miscellaneous “other” category for a moment, medical providers lead the pack in terms of both the number of reported incidents and the number of records affected. Government and the financial industry vie for second and third. Just out of the running is education. This is the strangeness in the proportions mentioned in the title of this column. A full 70% of the breach instances, and 64% of the compromised personal records, are produced by trusted institutions. Weren’t the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) and Gramm-Leach-Bliley (GLB) supposed to prevent these sorts of problems? - A final word on the “other” category. One of the weaknesses of descriptive statistics is that it ignores the distortions produced by occasional outliers. Such was the case here as 1.3 million records of “other” was the result of the Gawker Media hack in December, 2010. Figure 4 gives the appearance that a 35% of the records fell outside the categories listed.

Think of these breach categories the next time your health care provider asks for your Social Security number, your university asks for your cell phone number, or your DMV wants to put your street address on your driver's license! Giving up such personal and private information in the absence of a compelling need to know is an invitation for abuse. Your local doc should have a reasonable expectation of being paid for services, not a reasonable expectation of being able to access your Social Security retirement account. The exceedingly bad idea of using SSN as a primary database key dates all the way back to 1943 when President Roosevelt (Executive Order 9397) extended it to U.S. Government databases. It didn't take long before the states and the private sector seized the opportunity to do likewise. And the subsequent privacy legislation has had little or no effect in undoing the damage. In the digital world, think WINO: [W]once in, never out. Ok, the “W” was a stretch.

There is a tendency in government agencies to support legislation, policies and regulations that serve their own convenience, rather than the interests of those being served. Some states now requires a SSN of every boat owner when it is registered because the state's Department of Wildlife, Fish and Game Division, etc., are required to participate in the “dead-beat dads and moms” programs. One may imagine the state's Attorney General requesting a SSN for this purpose under some rubric or other, but the Department of Wildlife? The fact that a dead-beat parent who is behind in child support has the chutzpah to buy a boat may offend us, but it doesn't justify exposing all boat owners to additional risk of identity theft. The principle of proportional risk is at issue. To feel otherwise, in my view, attributes to the Wildlife/Fish and Game IT infrastructure a level of IT security that seems unjustified from my experience.

As the infamous Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction proved this past November, the U.S. Congress isn’t the collection of team players one might hope for. This surfaces in many ways, not the least of which is the final form of major legislation after sundry lobbyists, political factions, myopic influence peddlers, and power brokers have their way with it – the original intent of a bill isn’t always clear from the final product. Such is the case with HIPAA, SOX and GLB. But the one common denominator in all three pieces of legislation is a privacy rule that requires the protection of nonpublic personal information. You sure couldn’t tell that from the data, above. Here’s a newsflash for Congress: the privacy provisions aren’t working well enough. Maybe it’s a time for a CTL-ALT-DEL and a restart.

From a technologists’ perspective, the indirect cause of these privacy breaches seems to be a weakness in the Constitution . Privacy – especially information privacy - is not a right of citizenship. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness - perhaps. Privacy? Not so much. While the Constitution offered some protection against government intrusion (at least until the Patriot Act era), the big threat in the Internet age comes from sources as different as CardSystems Solutions, Heartland Payment Systems, TJ Maxx, Sony Online Entertainment, the local DMV, the New York Yankees, the Atlanta YMCA, and Google.

Legal scholars have discussed the consequences of the neglect of privacy guarantees for many years. Future Supreme Court Justice Brandeis and his law partner Samuel Warren suggested some remedies to this deficiency in their seminal Harvard Law Review in 1890! They were concerned about the loss of privacy that might result from the hand held camera. They wrote “Political, social, and economic changes entail the recognition of new rights…” – had they anticipated the Internet, they would have added “technology” to the list of changes, and spoken of information self-determination. It's pretty clear now that we have failed to pay heed to Warren and Brandeis' advice with the consequence that by the time that HIPAA, SOX, and GLB were put into law, the personal privacy toothpaste was already coming out of the common law tube. Patchwork attempts to ameliorate have met with mixed success. Montana guarantees the right to privacy in their constitution, and California's constitution considers privacy as an inalienable right. California has lead the way with state privacy protections with their breach notification and “shine the light” laws. My own state, Nevada, has joined Minnesota and Washington to require PCI DSS compliance of merchants who engage in credit card transactions. These are all worthy efforts, but as recent history has shown, they're not effective enough without the backing of Constitutional guarantees. By the time the safe harbor provisions of the law is added to capricious enforcement and confusing jurisdictional issues, the patchwork approach just doesn't work. The Congress is considering federal legislation, but based on past experience the likelihood that common sense will win out over the interests of the special interests is small.

What would it take to fix the problem in the absence of a Constitutional guarantee? I don't know, but accountability and a reality check or two would be a good place to start. How about a “hold harmful” clause to the effect that if you collect personal information on others that leads to their economic disadvantage, you are legally and financially responsible for the consequences. That would appeal to the business community like halitosis in a space helmet. But after the pro-forma hue and cry, modern commerce would probably find a way to go on. As for reality checks, let's start with the recognition that Albert Gonzales' of the world are not the problem, they're the symptom of the problem.

Absent this, we will have to count on cherished institutions like our colleges, health care professionals, banks, and governments to protect our privacy. NOT!

For additional detail on the Atlanta YMCA lost computer incident, see http://www.ajc.com/news/dekalb/ymca-says-someone-stole-1236919.html . A copy of the letter sent to the members quoted above appears at http://media.cmgdigital.com/shared/news/documents/2011/11/21/YMCAletter.pdf .

There is no shortage of studies on the size of the identity theft and financial fraud problem. Unfortunately, some of the best require corporate membership. Here are a few links that may provide a useful introduction:

For a more thorough analysis of an earlier reporting period, see Amit Grover, Hal Berghel and Dennis Cobb, The State of the Art in Identity Theft. In Marvin V. Zelkowitz, editor: Advances in Computers, Vol. 83, Burlington: Academic Press, 2011, pp. 1-50. The website for the Identity Theft and Financial Fraud Research and Operations Center is http://www.itffroc.org .

Finally, I wish to acknowledge my research assistant, Anthony Flarisee, for assistance with data collection and analysis.