accesses since January 3, 2006

accesses since January 3, 2006

copyright notice

copyright notice

link to published version: Communications of the ACM, April, 2006

link to published version: Communications of the ACM, April, 2006

accesses since January 3, 2006

accesses since January 3, 2006

Hal Berghel

The following definition from the Antiphishing Web site ( www.antiphishing.org ) is a useful place to begin.

| What is Phishing and Pharming? Phishing attacks use both social engineering and technical subterfuge to steal consumers' personal identity data and financial account credentials. Social-engineering schemes use 'spoofed' e-mails to lead consumers to counterfeit websites designed to trick recipients into divulging financial data such as credit card numbers, account usernames, passwords and social security numbers. Hijacking brand names of banks, e-retailers and credit card companies, phishers often convince recipients to respond. Technical subterfuge schemes plant crimeware onto PCs to steal credentials directly, often using Trojan keylogger spyware. Pharming crimeware misdirects users to fraudulent sites or proxy servers, typically through DNS hijacking or poisoning. |

The phish mongers to which I refer are those who deploy these phish scams in such a way that they stand a measurable chance of success against a reasonably intelligent and enlightened end-user. The posers are the bottom-feeders in the phishing community that exhibit a very low level of sophistication. This distinction is critical if one attempts to thwart phishing.

PHISHING ILLUSTRATED

There's more to phishing than throwing digital bait on the net. All too often descriptions of phishing scams drill down into deceptive URLs, fake address bars, and the like but fail to investigate the set-up that precedes the sting.

The sine-qua-non of effective phishing requires that the bait:

The similarities with angling should not be overlooked. There are reasons why anglers neither troll with charcoal briquettes nor fly-fish for sharks. We illustrate the analogy to the digital surf with a few illustrations taken from one of the phishing research projects in our lab.

Figure 1 is modeled after some live phish we captured on the net. Let's analyze this in terms of our five criteria. First, the email looks real - at least to the extent that it betrays nothing suspicious to a typical bank customer (aka target-of-opportunity). The graphic appears to be a reasonable facsimile of a familiar logo, and the salutation and letter is what we might expect in this context.

Second, the target is the subset of recipients who are Bank of America customers. The fact that the majority of recipients are not is not a deterrent because there's no penalty for over-phishing in the Internet waters. Third, the request seems entirely reasonable and appropriate given the justification. We reason that if we were a bank, we might do the same thing. Fourth, the URL-link seems to be appropriate to the brand. The unwary among us might readily trade off any lingering disbelief for the opportunity to correct what might be a simple error that could adversely affect use of a checking or credit card account. We may assume that the link to “verify.bofa.com” would take us to an equally plausible Web form that would request an account name and password or pin.

Figure 1. Phishing email that satisfies our four effectiveness criteria.

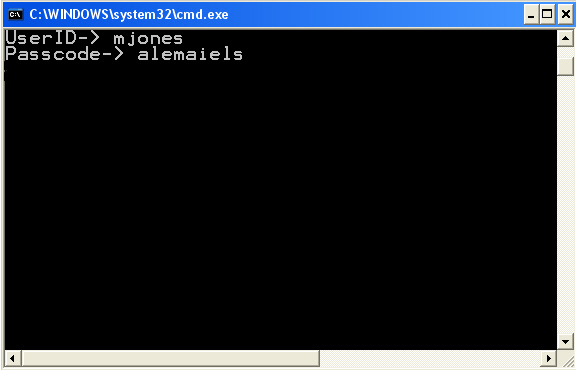

The unwary in this case is M. Jones whose harvested Web form appears to the phisherman as in Figure 2. This is a screenshot of an actual phishing server in our lab..

Figure 2: Phishing from the phisherman's perspective

In order to complete the scam the fifth condition must apply. In this case, after the private information is harvested, the circle is completed when the phishing server redirects the victim to the actual bank site. This has the effect of keeping the bank's server logs roughly in line in case someone makes an inquiry of the help desk.

Figure 3 illustrates this activity. Of course, a more careful inspection of the banks server logs would reveal a flaw in this simplified approach, because the phishing server shows up in as the “referrer” – a telltale sign the phisher would like to avoid. But, this deficiency could be overcome by a bit of careful packet crafting.

Figure 3. Phish Clean-up

THE POSERS AMONG US

The example above is a well-known exploit strategy. Some sub-cerebral variations on this theme appear below.

Example #1: from the 218.12. class B network registered to an ISP in Beijing

GIST OF EMAIL: A U.S. bank admits that its database has been hacked. The bank needs to have your bank debit card number, account ID, and PIN immediately. NOTABLE QUOTES: “This process is mandatory, and if you did [sic] not sign on within the nearest time [sic] your account may be subject to temporary suspension.” PHISHING LINE: http://218.12.29.40 TARGET-OF-OPPORTUNITY: Someone grammatically-challenged, especially with respect to tense and adjectives, who is both a fan of online banking and newbie to the Web. EFFECTIVENESS CRITERIA SCORE: .5 out of 5. |

2. from the 80.53 class B registered to an ISP in Gdansk .

GIST OF EMAIL: An eCash service claims to have noticed attempts to log in to the user's account from a foreign IP address. NOTABLE QUOTES: “...we have reasons to belive [sic] that your account was hijacked by a third party…. If you choose to ignore our request, you leave us no choise [sic] but to temporaly [sic] suspend your account.” PHISHINGLINE: click here TARGET-OF-OPPORTUNITY: Submissive types who click on anything when told to do so and also subscribe to the school of relaxed orthography. EFFECTIVENESS CRITERIA SCORE: 1 out of 5 is charitable. |

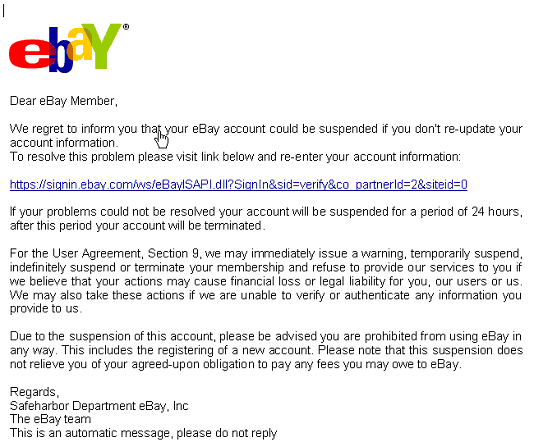

3. from an IP in Russia operating through a Web hosting service in Jordan

GIST OF EMAIL: A well-known Web auction company's Departament [sic] indicates that their records are out of date and that billing NOTABLE QUOTES: “Departament” is just a start. How about “Please update your records in maximum 24 hours.” PHISHINGLINE: Please click here to update your billing records. However, a look at the source page shows the actual URL is <a href="http://darkcity.ru/acounts/memb/avncenter/dll87443/.BayISAPI.dll/ hgdas676bsda6gwcv7zfcwfcwf34gfwf23g235f134f3fg3f&bhdfahva68532hbhwseBayISAPI.dllPaymentLanding&ssPageName= TARGET-OF-OPPORTUNITY: People who like lots of vowels who don't know how to use the “view source” menu option in their browser EFFECTIVENESS CRITERIA SCORE: 1.5 out of 5 seems generous to me. |

MONGERS AND MAYHEM

So much for posers. My last example is a phish of a different stripe. So much so that it justifies discussion. It comes to us through an ISP in Shanghai in a cleverly disguised way.

Figure 4: Phish Mongering

Look carefully at the cursor in Figure 4. The cursor seems to be sensing the link even though it's not particularly close to it. The fact is that it's not sensing the link at all, but rather an image map. A quick review of the source code, below, leads us to a veritable cornucopia of trickery.

<x-html>

<html><p><font face="Arial"><A HREF="https://signin.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?SignIn&sid=verify&co_partnerId=2&siteid=0"><map name="xlhjiwb"><area coords="0, 0, 646, 569" shape="rect" href="http://218.1.XXX.YYY/.../e3b/"></map><img SRC="cid:part1.04050500.04030901@support_id_314202457@ebay.com" border="0" usemap="#xlhjiwb"></A></a></font></p><p><font color="#FFFFF3">Barbie Harley Davidson in 1803 in 1951 AVI

</x-html>

Several features make it interesting. First, the image map coordinates take up pretty much the whole page. Second, the image that is mapped is the actual text of the email. So what appeared to be email was just a picture of email. Thus, the redirect was actually not a secure connection to eBay at all as it appeared, but an insecure connection to 218.1.XXX.YYY/.../e3b/. While Windows users see the “dots of laziness” frequently when path expression is too long for the path pane in some window, this isn't a Windows path in a path pane. These “dots of laziness” are a directory name. Now why would one create a directory named “…” It certainly falls short of the mnemonic requirements most of us learned in intro to programming.

On the other hand, it might blend in stealthily with the other *nix hidden files, “.” and “..” and possibly escape an onlooker's suspicion. This suggests that the computer at the end of 218.1.XXX.YYY may not be the phisher at all, but another unsuspecting victim whose computer has been compromised (for that reason, I've concealed the final two octets of the IP address.). Another sign of intrigue is the font color of almost pure white “#FFFFF3” for “Barbie Harley Davidson in 1803 in 1951 AVI.” Though their names are sullied, neither Barbie nor Harley Davidson had anything to do with this scam. This white-on-white hidden text is there to throw off the Bayesian analyzers in spam filters. Note that the email text is actually a graphic, so the Baysian analysis likely concludes that this is about Barbie and her Harley.

As opposed to the posers, this phish monger is moderately clever. While the exploit may not earn a trophy, it's a keeper.

CONCLUSION

It is unfortunate in the extreme that there are victims who fall for the fatuous phishing scams. We would all sleep sounder if the kind of flagrant errors characterized by our posers automatically ruled them out of all consideration. But they don't, more's the pity. Unlike cracking and the business of script kiddying, phishing is economically motivated: if it weren't profitable for these cyber crooks to phish, they wouldn't do it. And if the posers are occasionally effective, it's no wonder that the Mongers account for economic losses in the billions of dollars each year – losses that are ultimately born by the customers.

All four examples, even those written by the posers, managed to escape detection by one of my spam/phish filters within the last few months. The likelihood is that future phishing, or whatever phoolware follows it, will continue the cat-and-mouse game with security software. Perhaps our greatest mistake is excessive reliance on technology solutions. Our efforts seem no more effective at blocking phish scams now than they were at blocking embedded executables 10 years ago.

When it comes to email, common sense still goes a long way.

URL PEARLS

The best starting point for phishing awareness is the Antiphishing Web site ( www.antiphishing.org ). This site contains useful statistics, charts, events lists, and archives of virtually all aspects of phishing as we know it collected by third party sources. Not surprisingly, their bar charts reveal that phishing is on the ascent. The statistics are unweighted so the impact of the major offending nations tend to be under-represented. More meaningful measures might include percentages of attacks as a percentage of registered IP addresses, percentage of Internet traffic, etc.

Fraudwatch International's Website ( www.fraudwatchinternational.com ) is a good place to start investigation of Phishing scams. It lists current alerts for both phishing and non-phishing scams, Internet fraud and identity theft. On a good day their Website will produce a dozen or two new phishing alerts. Since phishing is propagated primarily through email, the lifespan of a phish scam is measured in days before they are included in malware and firewall updates. Consequently, only the most recent reports are represent those variations on the theme that are the most dangerous. As of this writing, there were 22,821 individual phishing exploits being monitored by Fraudwatch, 590 of which are currently active. Fraudwatch also offers Fraudshield, a phish-filtering utility that works much like an anti-virus program.

For a historical perspective on email, see my April, 1997 CACM column “Email: the good, the bad and the ugly.”

Hal Berghel is an educator, administrator, inventor, author, columnist, lecturer and sometimes talk show guest. He is both an ACM and IEEE Fellow and has been recognized by both organizations for distinguished service. He is the Associate Dean of the Howard R. Hughes College of Engineering at UNLV, and his consultancy, Berghel.Net, provides security services for government and industry.